Some insights about "Insights"

Words should have meaning, accuracy should be valued, coherence should matter

Earlier this month, the Los Angeles Times renamed their opinion section “Voices” and added AI-generated “insights” to many of their opinion pieces. These “insights,” readers learn when they scroll to the bottom of the article, include a “viewpoint analysis” that rates the article on the scale from “right” to “left” and “perspectives” that summarize the piece and offer “alternate opinions” on the topic at hand.

According to the owner of the Los Angeles Times, a goal of these new features is “to help readers navigate the issues facing this nation.” A month in, I’m not the only one to have questions about this project.

In an article over at the Nieman Lab, Joshua Benton analyzes the problems with the right-to-left spectrum analysis, arguing that this type of rating is actually “destructive to democratic discourse.” Benton interviewed Lilliana Mason, a Johns Hopkins political scientist, who makes the case against this type of categorization:

The social psychology research really demonstrates that, when people read information that they think is coming from ‘their team,’ they are much more likely to immediately accept it... they’re even willing to change their own opinion in order to match their team’s when that occurs. So if you want your opinion pages to be persuading people, then this tool is doing the opposite.

In other words, if your goal is to help readers “navigate the issues facing this nation,” you’re not likely to achieve that by telling them whether an article aligns with their team or not.

But what if at least some readers are open to changing their minds? Might the Perplexity AI-generated “perspectives” below the viewpoint ratings introduce them to the broader conversation and offer them insights they might otherwise miss? I’ve spent some time reading through these “perspectives” and clicking on the sources that are cited in each section, and so far, I can tell you there isn’t a lot of actual insight available.

Here’s an example: On March 14, the paper published an opinion piece by a Steve Oney about the battle brewing over attempts to defund NPR. Oney is the author of a book about NPR, and his piece looks at the history of battles over funding of NPR and discusses where NPR stands now.

Scroll down to the bottom of the piece, and you’ll find that the AI tool labeled this piece “center left.” Maybe if you found common ground with the author but lean right, you’ll like the piece. But maybe you’ll just dismiss it because you don’t like the other team.

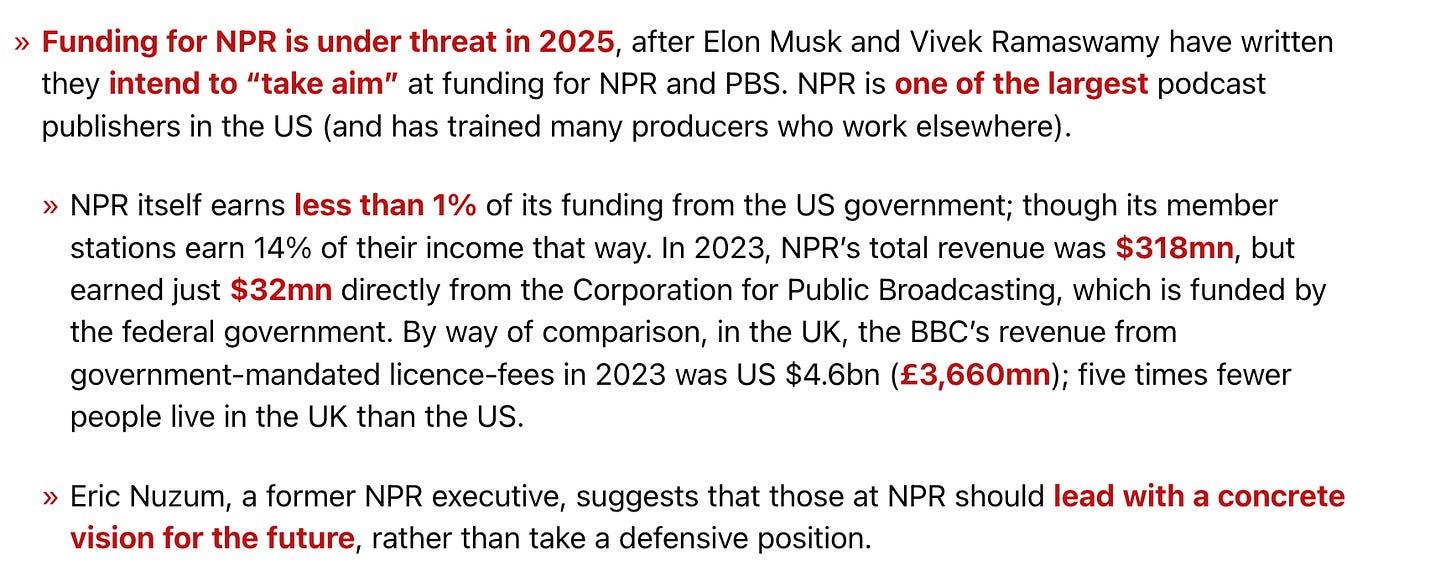

But maybe you’ll look further into those AI-generated insights to learn about the “different views on the topic” that Perplexity has to offer. In that case, you’ll see this:

You may read that paragraph and think, yeah, that “two-step funding shuffle” seems like a problem opponents could emphasize! Or you may think, I have no problem with that “two-step funding shuffle” and the money should keep flowing! But if you click on the links to the sources “cited” there, you’ll find they don’t mention the concept of the “two-step funding shuffle.” Yes, it’s in quotes in “Insights.” No, those words don’t appear in either source. They also don’t appear in the sources cited elsewhere in “Insights,” which do include a long article that does include some alternative viewpoints.

The first cited source in that passage is a post from podnews.net, an Australian news site, called “NPR Funding Under Threat,” which mentions NPR in this passage:

If you read that passage, you’d be able to figure out that member stations get more money from the government than the national station. But you’d have to look elsewhere to hear what “proponents of defunding” think about that. In fact, this article turns out to be focused on what NPR should do to maintain its funding—and illustrates how much more money the BBC gets.

What about the second article? That one is from Arizona Public Media. You can tell from the subheading that this, too, is not an article by “proponents of defunding.”

In fact, the article begins with a disclosure that AZPM receives 15% of its funding from the government and goes on to focus on the fact that rural and tribal stations receive up to 85% of their funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. This piece does contain a few sentences that summarize the views of the “proponents of defunding”—including a quote from US Representative Claudia Tenney, who introduced a defunding bill: “Taxpayer dollars should not fund political propaganda disguised as journalism.” So, in that sense it’s a source for another viewpoint—but not a source for the quotation about the “two-step funding shuffle” or the whole idea that local stations use their funds to buy national programs.

So neither source listed by Perplexity as a source for these “insights” includes the quote. In fact, when I turned to Google for the source of this “two-step funding shuffle” quotation, the only source I found was the AI-generated “insight” itself. Maybe it does exist somewhere, but even then, this will still be true: readers of this “insight” will assume the point comes from the sources cited, and it doesn’t.

If you’re reading this newsletter, you’re likely familiar with AI hallucinations, but readers of a news source may assume that what they’re being given is accurate and that it’s going to somehow augment their understanding of the original article. The AI perspectives here lack enough context to do that—and worse, they could actually make our understanding of the issues fuzzier.

Does any of this matter? After all, as Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arrellano wrote recently about the AI insights, “you have to press a button to trigger the thing. Like the comments section, you can engage with it or not. You can choose just to read what the humans have to say — and criticize or laud them.” And he’s right—it would be a lot easier to just ignore these “insights” than it is to read my MANY words walking you through this one example. But I wrote all these words because I think it’s worth asking ourselves what we’re doing here—and whether we should be ignoring or minimizing any of these AI features.

Whatever the Los Angeles Times owner’s reasons for adding this feature, here’s one effect of adding opposing viewpoints to the bottom of an opinion piece: It suggests that we should not necessarily expect opinion writers to introduce or acknowledge other points of view in the process of making their own arguments. But, of course, we know that good arguments do engage with counterarguments—and link to other pieces—and they also situate ideas in larger contexts. If a publication is concerned about making sure opinion pieces are strong, why not focus on…making opinion pieces stronger?

In this case, the original piece actually does offer insight into other perspectives—as it should. In the article, we learn that, in fact, local stations do spend some of their funding on NPR programs (although we don’t get the “two-step shuffle” phrasing there either!). The author writes this:

When we add AI tools to the mix without considering whether they actually do what is being promised, we’re not just adding another potentially useful tool that can be ignored if it’s not useful—we’re changing the way readers expect to engage. Instead of encouraging readers to expect an opinion piece to contain context and address other perspectives, the Los Angeles Times is setting a different expectation: that “someone from one political viewpoint will say something in a vacuum and then AI will situate that in a conversation with other voices from other political ‘teams’ who also speak in vacuums.” This would trouble me even if the AI tools did a better job; it troubles me more because they don’t.

The addition of AI-generated text to supplement human text, of course, isn’t just happening at the Los Angeles Times. In a very short time we’ve become accustomed to seeing AI-generated summaries of customer reviews on sites like Amazon, and we’ll no doubt be seeing more projects like the recently announced AI-generated news briefs created from Independent articles. Some of these projects may turn out to have benefits—but all of them are worth questioning.

We can skip the AI-generated “insight” or the “review” or the “summary” if it’s not useful. But we shouldn’t ignore how the presence of this additional text shapes how we engage with the original text. Here’s what we stand to lose, whether we personally choose to engage with “Insights” or not: the idea that the people making the arguments should also discuss and engage with counterarguments; the assumption that words should have meaning; the belief that accuracy is something to value; the conviction that coherence matters; and the expectation that actual engagement is different from the appearance of engagement. These are losses we simply can’t afford, especially now.

Check out The Important Work

Earlier this year, I launched a second newsletter, The Important Work, that features different authors sharing how they’re grappling with AI in the writing classroom. We often hear that generative AI is going to take on the menial tasks and free our time so that we can focus on the “important work.” But for those of us who teach writing, the writing has always been the important work, which raises questions about what teaching writing looks like now and what that important work actually is.

If you’re interested in reading or contributing or subscribing, you can find more information here.

![Proponents of defunding assert that NPR’s minimal direct federal reliance (1% of its budget) masks a deeper dependency, as member stations use CPB grants to purchase national programming—effectively funneling public money indirectly[1][4]. This “two-step funding shuffle” is labeled disingenuous by opponents who view it as circumventing accountability[1][4]. Proponents of defunding assert that NPR’s minimal direct federal reliance (1% of its budget) masks a deeper dependency, as member stations use CPB grants to purchase national programming—effectively funneling public money indirectly[1][4]. This “two-step funding shuffle” is labeled disingenuous by opponents who view it as circumventing accountability[1][4].](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!bcGR!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff62b164e-8059-4e02-8716-8d7c8ee8a55a_1054x214.png)