When the friction is the point

Writing is hard, but we may miss having written

When I first launched Writing Hacks during the pandemic, my goal was to provide actionable advice for writing effectively at work. Since the launch of ChatGPT, the conversation about writing has changed, and I’ve focused recent newsletters on making sense of those changes. Many of my newer subscribers have found me through my AI articles, and I’m so grateful that you’ve signed up. While today’s post is another one about writing and AI, I plan to continue to share advice about writing both with and without AI in future posts.

This week’s Hack: With writing, sometimes the friction is the point.

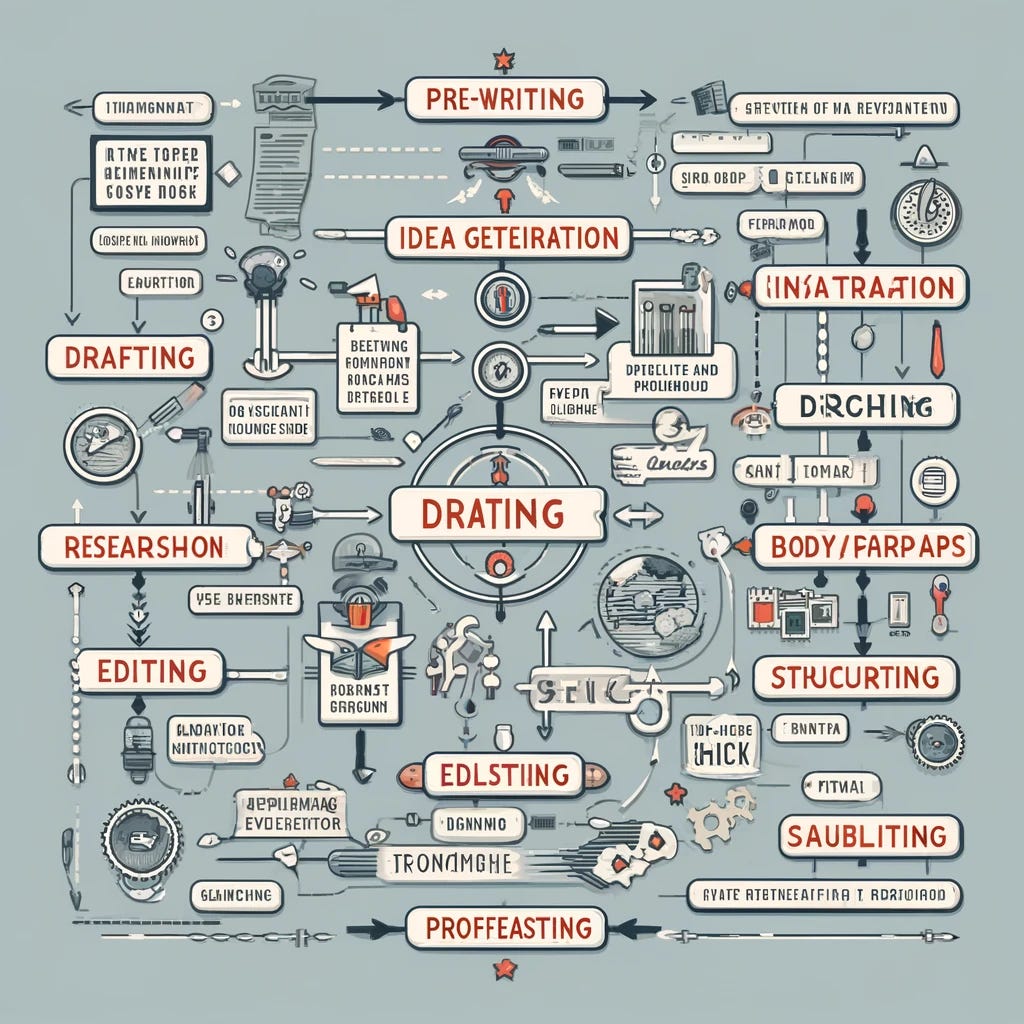

Last week I published an essay in the Boston Globe sparked by OpenAI’s recent announcement that they will now offer their most advanced version of ChatGPT free to all. OpenAI’s CTO, Mira Murati explained that “We’re always trying to find ways to reduce friction so that everyone can use ChatGPT wherever they are.” Murati was talking about the “friction” of having to pay for ChatGPT. But her announcement left me thinking about how ChatGPT—and other AI tools—promise to reshape our relationship to writing by removing the friction from every step of the writing process.

The writer Dorothy Parker probably never said “I hate writing. I love having written.” But the sentiment resonates, no matter who said it. Writing is hard, and it’s not surprising that the promise of removing that friction from the writing process is appealing. But we need to be able to recognize when removing the friction from the process might mean losing something important. We may love having written for different reasons, but the friction contributes to that feeling of satisfaction. I love having written when I am able to give structure to my thoughts or discover something in the process of writing that is satisfying or even profound—when I find an answer or solve a problem or arrange words in a way that makes me see something more clearly.

As a writing instructor, I make decisions all the time about when I want students to work through that productive friction and when I want to step in to help. It’s great to get help, but sometimes help isn’t what we need. I try to help them distinguish between the productive friction of the writing process and the less productive friction of being stuck.

In the age of AI, we’re going to have to decide when we want to use these tools, when they remove productive friction, and even when they may bring new and useful friction to the process. I’ve written before about questions to ask when you’re deciding whether to use AI in your writing process. Is the output helpful? Do you know enough about what you’re trying to do to judge the output? Do you know about hallucinations and bias in LLM output? In addition to those questions, we need to pay attention to whether anything is lost when we remove the friction from different steps in the process. This will depend on your writing goals and the technology available. Writing is hard, but I fear we may miss having written.

I’m including my Globe article below, but first, some AI news: You may have heard that Google’s AI overview is coming up with some unusual results. Here’s one that I got the other day. (Be careful out there!)

As always, please share your thoughts in the comments or send me a message!

Globe article

Last week’s demo of OpenAI’s latest voice chatbot created so much hype (It can translate languages in real time! The initial version sounded like a flirty imitation of Scarlett Johansson in the movie “Her”!) that it was easy to miss the significance of an announcement that came early in the event. Chief technology officer Mira Murati announced that OpenAI will soon offer its most advanced model (which is known as GPT4o and includes voice chat) for free. “We’re always trying to find ways to reduce friction,” Murati said, “so that everyone can use ChatGPT wherever they are.”

The decision to offer the advanced model for free “to reduce friction” was a fitting move for a company that seems to be on a mission to reduce or remove the friction from so many aspects of our lives. After all, just a few weeks ago, CEO Sam Altman described the ideal ChatGPT app as “a super-competent colleague that knows absolutely everything about my whole life, every email, every conversation I’ve ever had, but doesn’t feel like an extension.”

For educators grappling with the implications of generative AI in the classroom, though, OpenAI’s decision to freely distribute its technology is going to worsen an already challenging situation.

Even those of us who are open to using AI in the classroom recognize that a tool capable of reducing (or eliminating) the friction that makes thinking, writing, and problem-solving challenging is often going to be at odds with the messy and difficult process of learning. Students need support, and it is possible that AI tutors like those championed by Khan Academy can play a positive role in offering that support.

But students also need opportunities to experiment, to learn to think for themselves, to follow their curiosity, and to make mistakes. What will that look like come September, when every student with a cellphone will have access to a voice chatbot that can do much of their schoolwork in seconds?

Up to this point, AI policies at both the K-12 and college levels have been scattershot. Some school districts have ignored chatbots entirely; many colleges have left decisions about AI up to individual instructors; some teachers have incorporated generative AI into some assignments or tried to redesign assignments to deter its use in cases where they want students to work on their own. But it’s becoming increasingly clear that educators can’t redesign their way out of a world in which students as young as those in elementary school will have GPT4o on their phones and a Gemini AI in every Google app on their school-issued Chromebooks.

Embracing AI in the classroom is not a simple decision. There are tasks a chatbot can do pretty well that we still want our students to do themselves, for good reasons. For example, the fact that ChatGPT can summarize and analyze an article that I feed it does not mean that I no longer want students in my writing course to read articles or analyze what they read. I don’t assign summary and analysis because I need more summaries or analyses; I assign these projects because I want to help my students think through complex ideas and grapple with them. And I don’t ask my students to write papers because the world needs more student papers; I assign papers because I want my students to go through the process of figuring out what they think. The friction is the point.

Ed-tech companies are rolling out chatbots with guardrails and assurances that student learning remains the priority. For example, Khanmigo promises that “unlike other AI tools such as ChatGPT, Khanmigo doesn’t just give answers. Instead, with limitless patience, it guides learners to find the answer themselves.” But even if this type of tool turns out to be useful, we have to accept that these tools don’t exist in a vacuum; they exist in the same world as the chatbot on your phone. It’s unreasonable to think that students will choose to use a chatbot only at moments when it would be an effective learning tool — and we shouldn’t expect them to know how to make such decisions.

Even if we explain why an assignment should be done without a bot, we can’t pretend that when students are stressed or busy or just bored, they’re not going to take this shortcut. It’s already happening. One middle school principal told me that “keeping up with the technology is overwhelming — just when we get a handle on it, the landscape changes.” Meanwhile, a November survey of K-12 educators found 79 percent of those surveyed said their school districts had no clear policies about the use of AI in the classroom. As recently as February, a survey of school superintendents found that only 37 percent had plans for training teachers in AI usage.

Part of the problem is that the conversation about AI in education has been dominated by the companies churning out AI tools rather than by the teachers in the classrooms. That means we started talking about how to use AI to teach or how to stop it from being used by students before we ever talked about why — and before teachers had the opportunity to become familiar with generative AI tools. Before we incorporate chatbots into every classroom, we should first be making sure that teachers at all levels have opportunities to learn about the strengths and weaknesses of chatbots. And we should be making space in the curriculum to help students understand how these tools work. AI tools, it turns out, are not frictionless. They hallucinate. They deliver the biases embedded in their training data. Using them comes with costs to our privacy and to the environment. To prepare students to live with AI, we can’t just teach them how to use chatbots; we need to teach them to think critically about using them.

This year I taught a college writing course called “To What Problem Is ChatGPT the Solution?” My students read and wrote about the world of generative AI that they are now living in. For their first assignment, I asked them to explain how generative AI works, for an audience of their choice. I told them that it was important to have a basic understanding of these tools before they start to rely on them. At the end of the course, some of my students told me they were more interested in using generative AI for various tasks in the future; others said they were less optimistic about how useful generative AI will be to them. But they all agreed that their decisions about how to use AI in the future would be informed by their knowledge of the costs and benefits.

I was teaching college during the first year that most students had access to these tools. In the future, students will arrive in college having had chatbots accompany them every step of the way. As AI developments advance, students at every level are going to need guidance on how — or if — they should incorporate these tools into their learning. We need to invest in making sure that teachers have the training to guide them — but more important, we need to stay focused on what we want students to be learning in the first place. Our students are not products to be moved down a frictionless assembly line, and the hard work of reading, writing, and thinking is not a problem to be solved.

We are definitely straddling a major dividing line - my colleagues are telling me, too, that they're meeting a cohort for whom the COVID period was critical for breaking down some of the old norms; building up new ones that meet traditional academic expectations is a major point of friction already, and now add in the chatbots? Whoo boy...

I have been using AI in my fiction writing for some time. It has been a huge game changer for me. Personally, I think it's a net positive for writers, but definitely proper training is required for writers to use AI effectively and ethically.