Writing and Learning to Write in the Age of AI

Three questions from your college writing teacher

I was grateful to be invited to give a talk at a generative AI conference at the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard Law School a few weeks ago. A few people asked me to share my slides, so I decided to write up a summary of the talk to go with the slides. My goal in this brief talk was to spark discussion about the idea that when we talk about outsourcing our writing to ChatGPT and other generative AI tools, we’re also talking about outsourcing our thinking.

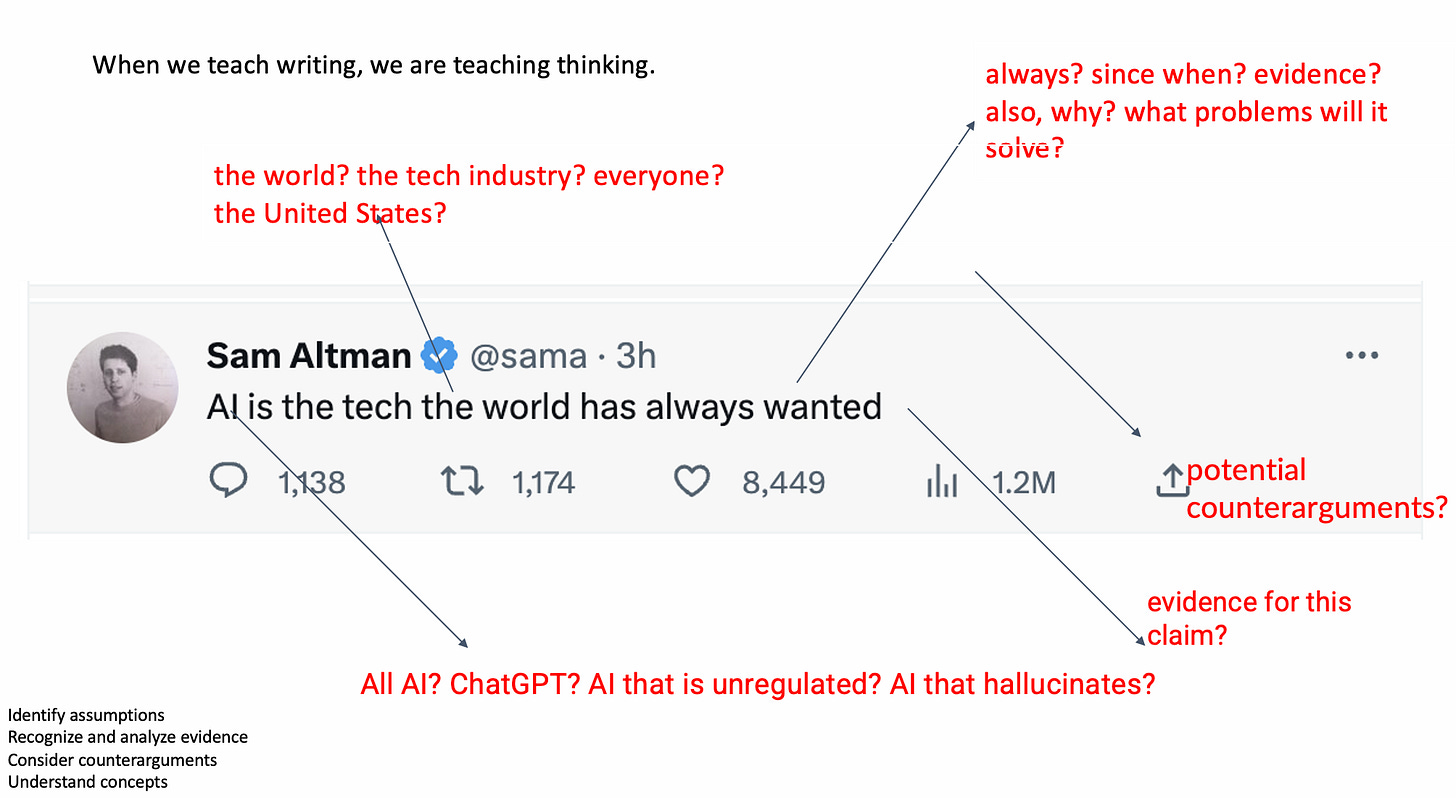

I began my talk with the slide below.

I annotated this tweet by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman to illustrate the questions that I would ask any student who made the claim that Altman makes here—that “AI is the tech the world has always wanted.” If one of my students made this claim, I would ask for evidence, for specificity, and for counterarguments. I would want to help them figure out what assumptions might have led them to this conclusion and how they might explain their ideas to someone who is not convinced. In other words, writing requires thinking—and when we teach writing, we are encouraging our students to go through a process of figuring out what they think.

When I showed this slide, I also highlighted the following points:

If we treat writing as a product that we can outsource, we miss that it’s in the process of writing that we figure out what we think.

In order to make sense of the hype surrounding ChatGPT and generative AI, we are going to need to the use the very critical thinking skills that we teach in writing courses.

I then raised the first of my three questions: What happens to critical thinking when AI does the writing?

I showed the slide below to illustrate two different potential outcomes:

The top quotation on this slide is from Owen Kichizo Terry’s article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, “I’m a student. You have no idea how much we’re using ChatGPT.” Terry, an undergraduate at Columbia, describes using ChatGPT to generate arguable claims, evidence for those claims, and outlines for his arguments. In other words, he describes outsourcing his thinking to ChatGPT and using it to create a product.

The second quotation, from the Khan Academy website, describes Khanmigo, their new “AI-powered guide.” While Terry presents a worst-case scenario for the way students might use ChatGPT, Khan Academy promises a best-case scenario. Their website suggests that rather than undermining the thinking process, their chatbot will facilitate student thought and learning. (For my concerns about this approach, see question #2 below).

If students are going to be encouraged to use AI as part of the writing process, we need to talk about whether it actually facilitates the process—or whether it allows us to bypass the process. To illustrate this point, I talked about brainstorming. I asked ChatGPT to brainstorm some possible critiques of Michael Sandel’s “The Case Against Perfection,” and I compared those to what come students came up with when I asked them the same question. Here’s the main difference: When the students did the brainstorming themeselves, they were doing their own thinking. The fact that ChatGPT could provide an answer to this question does not mean that it is no longer valuable for my students to answer it themselves.

With that in mind, I raised my second question: How will using AI in the writing classroom impact imagination, originality, and our ability to think independently?

We have heard claims from a number of sources that generative AI will make us more efficient, but also enhance our thinking and creativity.

I pulled the quotation “ChatGPT solves the blank page problem” from a Times article about how people are using ChatGPT. Others have told me that they find it useful for this reason. But we also need to think about whether being alone with your own thoughts is valuable—and what we might lose if we start from a bot-generated set of thoughts rather than from our own. I also gave the example of a new app called SmartDreams that promises to help kids write their own bedtime stories in a way that is, according to its founder, “as easy as selecting a few key elements.” I raised the question of what this type of app might mean for encouraging creativity and imagination.

I also mentioned the example of the office at Vanderbilt that sent out an email after the Michigan State University shooting that, they noted at the bottom of the text, had been generated using ChatGPT. It turned out that in that situation, students wanted to hear actual thoughts from a human.

Finally, I shared a quotation from Sal Khan’s recent TED talk about AI and Khan Academy. He talked about how AI allows students to interact with fictional characters and ask them questions. In the example, the student asks Gatsby, “Why do you keep staring at the green light?” and was excited to receive this answer: “Ah, the green light, old sport. It’s a symbol of my dreams and desires, you see. It’s situated at the end of Daisy Buchanan’s dock across the bay from my mansion. I gave at it longingly as it represents my yearning for the past and my hope to reunite with Daisy, the love of my life.” I raised the question of whether it is win for creativity to have a chatbot version of Jay Gatsby answering an exam question that he would never answer.

That discussion brought me to my third and final question: What should happen to writing instruction (and writing) in the age of AI?

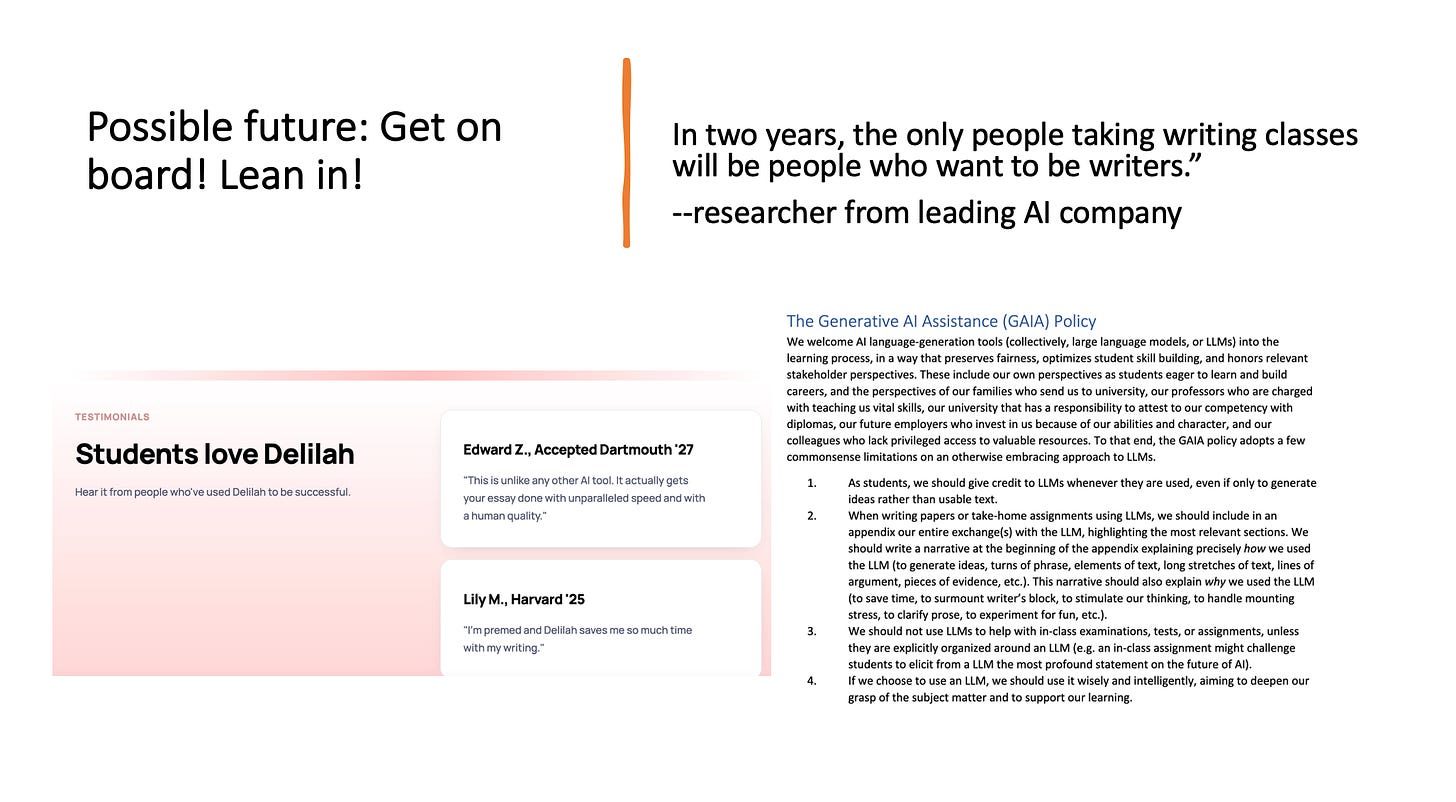

One possible future we’ve been offered is the one in which embracing this technology is inevitable. In this future, we either get on the ChatGPT train, or we’re left behind. I understand this approach. It’s hard to imagine a future in which these tools are not widely used. That view has sparked policies, products, and punditry. A thoughtful group of students and faculty in computer science at Boston University took that approach when they wrote a generative AI policy. Companies are springing up to create tools that they promise will make us more productive—and sometimes more creative—including a student start-up called Delilah, pictured below. And rather ominously, an AI researcher told me back in December that in two years, the only people taking writing classes would be people who want to be writers.

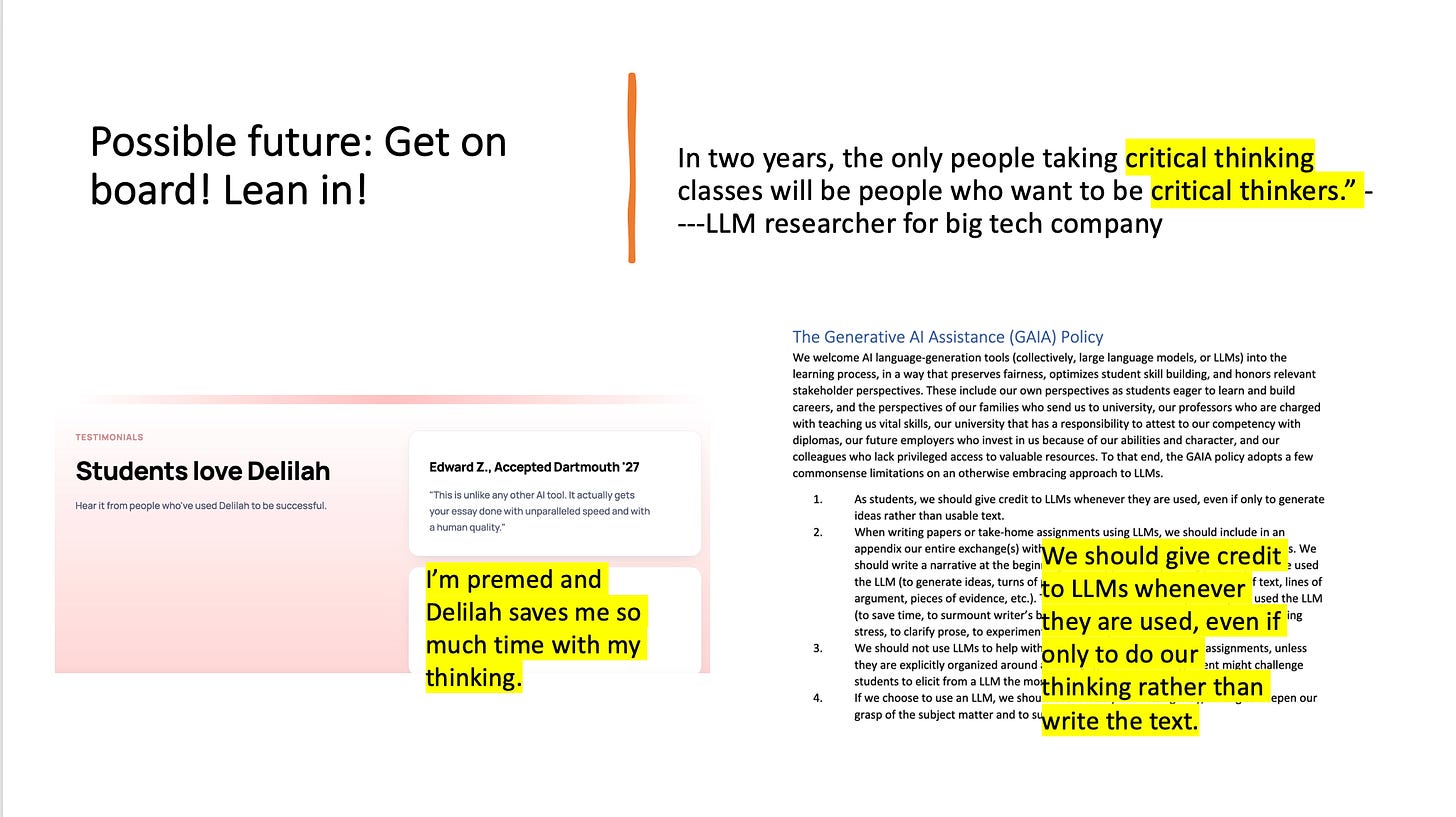

But I don’t believe that a future in which no one writes is inevitable—or desirable. I think a useful way to reframe this is to talk in terms of thinking rather than in terms of writing. In the slide below, I replaced the word “writing” with “thinking” to raise the question of whether that changes how we think about AI.

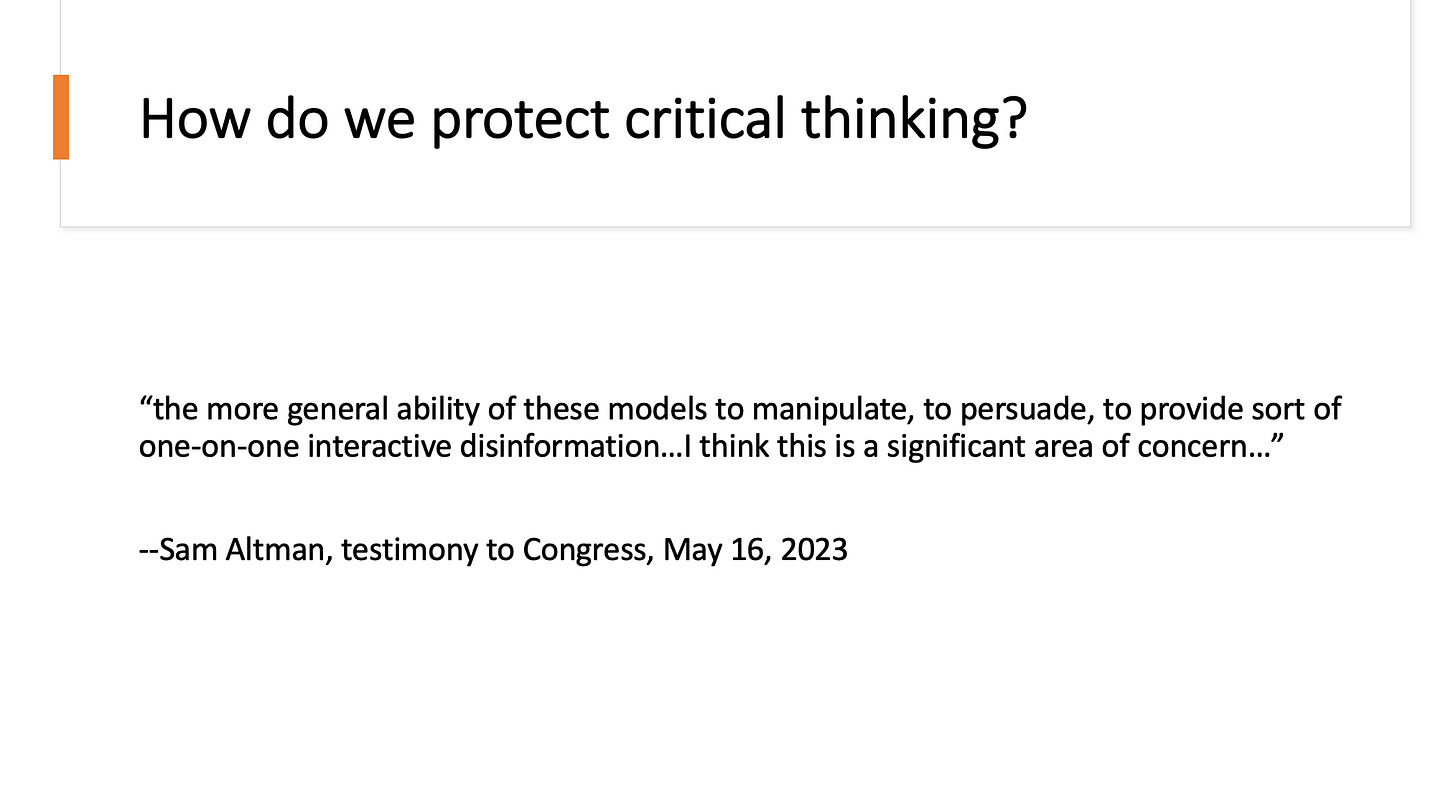

My purpose in this talk was to raise questions rather than to answer them. But I did return to the point that the we all seem to agree on: We are in uncharted territory with generative AI. With that in mind, I hope we don’t accept the idea that outsourcing our thinking is either desirable or inevitable.

My final slide:

Excellent post! I think this question can go even deeper and wider, with respect to thinking and education. For example, “Is there a certain age when introducing AI is appropriate?”; “When we ask AI to summarize text what are we losing?”; “Do our goals for learners need to change?”; and if so “What then are our new learning goals?”. All I know is that I do not want to live in a world where thinking is no longer a vital human condition.

Excellent starting point for a discussion with teenagers.